|

he Executive Clerk's

Office is one of the oldest within the White House, serving in support of the

Presidency for more than 140 years. Among the earliest Executive Clerks was

William Henry Crook, a former bodyguard of President Lincoln, who began his

duties in 1865 and went on to serve in the White House for more than 40 years. he Executive Clerk's

Office is one of the oldest within the White House, serving in support of the

Presidency for more than 140 years. Among the earliest Executive Clerks was

William Henry Crook, a former bodyguard of President Lincoln, who began his

duties in 1865 and went on to serve in the White House for more than 40 years.

The Executive Clerk's Office is responsible for the preparation, review, and

final disposition of official documents signed by the President, such as

executive orders, proclamations, messages to Congress, and memoranda to the

various units within the executive branch. The office also receives all formal

documents sent from the Congress to the President, including Senate confirmation

resolutions, resolutions to the ratification of treaties, and enrolled bills

passed by the Congress for the President's action. The Constitution states that

when the Congress delivers a bill to the White House, the President has ten

days to act on the bill. If the President signs the bill, it becomes law. If he

vetoes it, it is the responsibility of the Executive Clerk to deliver the bill

back to the Congress for reconsideration.

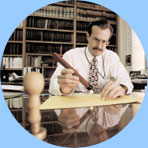

Tim Saunders, the Executive Clerk, prepares a wax seal for an important document

from the President to Congress.

|

The current Executive Clerk, Tim Saunders, began working in the Executive

Clerk's Office during President Jimmy Carter's Administration. In 1994, he

became the tenth Executive Clerk in White House history. You may have seen

Mr. Saunders if you have visited the United States Capitol or if you have

watched the Congress in session on television. Whenever the President has a

message or some other important communication for the Congress, Mr. Saunders or

another staff member from the Executive Clerk's Office must deliver the message

in person. Before leaving the White House for Capitol Hill, the Clerk places

the President's message in a special envelope, seals the envelope by heating

red wax onto the flap, and then stamps the wax with a die of the President's

Seal, creating the distinctive impression that identifies the document as a

Presidential message.

When delivering a message to the House of Representatives, the Executive Clerk

participates in one of the oldest continuing traditions within our government.

When the Clerk is introduced on the House floor, the proceedings are

interrupted. The Clerk then formally bows and announces, "Mr. Speaker, I am

directed by the President of the United States to deliver a message in writing."

He then leaves the envelope containing the message and returns to the White

House.

Colonel William Henry Crook (far left), who served as President Lincoln's bodyguard and the first Executive Clerk, poses with staff from the McKinley Administration.

|

Tim Saunders carries on a proud tradition of service at the White House. His

office is filled with mementos and photographs from the Executive Clerks who

came before him, and he enjoys telling young visitors about the history of his

office and the unique role he plays within the White House.

|