Republic of Guatemala

Profile

Profile

History

Government

Politics

Economy

Foreign Relations

U.S.-Guatemalan Relations

|

Republic of Guatemala

|

|

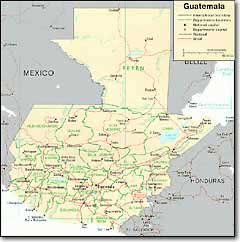

Geography Area: 108,780 sq.

km. (42,000 sq. mi.); about the size of Tennessee. People Nationality: Noun

and adjective--Guatemalan(s). Government Type: Constitutional

Democratic Republic. Economy GDP (1997 est.):

$16 billion. More than half of Guatemalans are descendants of Mayan Indians. Westernized Mayans and mestizos (mixed European and Indian) are known as ladinos. Most of Guatemala's population is rural, though urbanization is accelerating. The predominant religion is Roman Catholicism, into which many Indians have incorporated traditional forms of worship. Protestantism and traditional Mayan religions are practiced by an estimated 30% of the population. Though the official language is Spanish, it is not universally understood among the indigenous population. However, the peace accords signed in December 1996 provide for the translation of some official documents and voting materials into several indigenous languages (see summary of main substantive accords). The Mayan civilization flourished throughout much of Guatemala and the surrounding region long before the Spanish arrived, but it was already in decline when the Mayans were defeated by Pedro de Alvarado in 1523-24. During Spanish colonial rule, most of Central America came under the control of the Captaincy General of Guatemala. The first colonial capital, Ciudad Vieja, was ruined by floods and an earthquake in 1542. Survivors founded Antigua, the second capital, in 1543. In the 17th century, Antigua became one of the richest capitals in the New World. Always vulnerable to volcanic eruptions, floods, and earthquakes, Antigua was destroyed by two earthquakes in 1773, but the remnants of its Spanish colonial architecture have been preserved as a national monument. The third capital, Guatemala City, was founded in 1776, after Antigua was abandoned. Guatemala gained independence from Spain on September 15, 1821; it briefly became part of the Mexican Empire and then for a period belonged to a federation called the United Provinces of Central America. From the mid-19th century until the mid-1980s, the country passed through a series of dictatorships, insurgencies (particularly beginning in the 1960s), coups, and stretches of military rule with only occasional periods of representative government. 1944 to 1986 In 1944, Gen. Jorge Ubico's dictatorship was overthrown by the "October Revolutionaries"--a group of dissident military officers, students, and liberal professionals. A civilian president, Juan Jose Arevalo, was elected in 1945 and held the presidency until 1951. Social reforms initiated by Arevalo were continued by his successor, Col. Jacobo Arbenz. Arbenz permitted the communist Guatemalan Labor Party to gain legal status in 1952. By the mid-point of Arbenz's term, communists controlled key peasant organizations, labor unions, and the governing political party, holding some key government positions. Despite most Guatemalans' attachment to the original ideals of the 1944 uprising, some private sector leaders and the military viewed Arbenz's policies as a menace. The army refused to defend the Arbenz Government when a group led by Col. Carlos Castillo Armas invaded the country from Honduras in 1954 and eventually took over the government. In response to the increasingly autocratic rule of General Ydigoras Fuentes, who took power in 1958 following the murder of Col. Castillo Armas, a group of junior military officers revolted in 1960. When they failed, several went into hiding and established close ties with Cuba. This group became the nucleus of the forces that were in armed insurrection against the government for the next 36 years. Three principal left-wing guerrilla groups--the Guerrilla Army of the Poor (EGP), the Revolutionary Organization of Armed People (ORPA), and the Rebel Armed Forces (FAR)--conducted economic sabotage and targeted government installations and members of government security forces in armed attacks. These three organizations, plus a fourth--the outlawed communist party, known as the PGT--combined to form the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity (URNG) in 1982. At the same time, extreme right-wing groups of self-appointed vigilantes, including the Secret Anti-Communist Army (ESA) and the White Hand, tortured and murdered students, professionals, and peasants suspected of involvement in leftist activities. Shortly after President Julio Cesar Mendez Montenegro took office in 1966, the army launched a major counterinsurgency campaign that largely broke up the guerrilla movement in the countryside. The guerrillas then concentrated their attacks in Guatemala City, where they assassinated many leading figures, including U.S. Ambassador John Gordon Mein in 1968. Between 1966 and 1982, there were a series of military or military-dominated governments. In March 1982, army troops commanded by junior officers staged a coup to prevent the assumption of power by former Defense Minister Gen. Anibal Guevara, whose electoral victory was marred by fraud. The coup leaders asked Brig. Gen. Efrain Jose Rios Montt to negotiate the departure of presidential incumbent General Lucas Garcia. Rios Montt had been the candidate of the Christian Democratic Party in the 1974 presidential elections and was also widely believed to have lost by fraud. Rios Montt formed a three-member junta that annulled the 1965 constitution, dissolved the Congress, suspended political parties, and canceled the election law. Shortly thereafter, Rios Montt assumed the title of President of the Republic. Responding to a wave of violence, the government imposed a state of siege, while at the same time forming an advisory Council of State to guide a return to democracy. In 1983, electoral laws were promulgated, the state of siege was lifted, political activity was once again allowed, and constituent assembly elections scheduled. Guerrilla forces and their leftist allies then denounced the new government and stepped up attacks. Rios Montt sought to combat the threat with military actions and economic reforms, in his words, "rifles and beans." The government formed civilian defense forces which, along with the army, successfully contained the insurgency. However, on August 8, 1983, Rios Montt was deposed by the Guatemalan army, and Minister of Defense, Gen. Oscar Humberto Mejia Victores, was proclaimed head of state. General Mejia claimed that certain "religious fanatics" were abusing their positions in the government and that corruption had to be weeded out. Constituent assembly elections were held on July 1, 1984. On May 30, 1985, after nine months of debate, the constituent assembly finished drafting a new constitution, which took immediate effect. Mejia called general elections. The Christian Democratic Party (DCG) candidate, Vinicio Cerezo, won the presidency with almost 70% of the vote and took office in January 1986. 1986 to 1996 Upon its inauguration in January 1986, President Cerezo's civilian government announced that its top priorities would be to end the political violence and establish the rule of law. Reforms included new laws of habeas corpus and amparo (court-ordered protection), the creation of a legislative human rights committee, and the establishment in 1987 of the office of Human Rights Ombudsman. The Supreme Court also embarked on a series of reforms to fight corruption and improve legal system efficiency. With Cerezo's election, the military returned to its more traditional role of fighting against the insurgents. The first two years of Cerezo's Administration were characterized by a stable economy and a marked decrease in political violence. Two coup attempts were made in May 1988 and May 1989 by dissatisfied military personnel, but military leadership supported the constitutional order. The government was heavily criticized for its unwillingness to investigate or prosecute cases of human rights violations. The final two years of Cerezo's Government also were marked by a failing economy, strikes, protest marches, and allegations of widespread corruption. The government's inability to deal with many of the nation's problems--such as infant mortality, illiteracy, deficient health and social services, and rising levels of violence--contributed to popular discontent. Presidential and congressional elections were held on November 11, 1990. After a runoff ballot, Jorge Serrano was inaugurated on January 14, 1991, thus completing the first transition from one democratically elected civilian government to another. Because his Movement of Solidarity Action (MAS) party gained only 18 of 116 seats in Congress, Serrano entered into a tenuous alliance with the Christian Democrats and the National Union of the Center (UCN). The Serrano Administration's record was mixed. It had some success in consolidating civilian control over the army, replacing a number of senior officers and persuading the military to participate in peace talks with the URNG. He took the politically unpopular step of recognizing the sovereignty of Belize. The Serrano Government reversed the economic slide it inherited, reducing inflation and boosting real growth from 3% in 1990 to almost 5% in 1992. On May 25, 1993, Serrano illegally dissolved Congress and the Supreme Court and tried to restrict civil freedoms, allegedly to fight corruption. The "autogolpe" (or autocoup) failed due to unified, strong protests by most elements of Guatemalan society, international pressure, and the army's enforcement of the decisions of the Court of Constitutionality, which ruled against the attempted takeover. In the face of this pressure, Serrano fled the country. On June 5, 1993, the Congress, pursuant to the 1985 constitution, elected the Human Rights Ombudsman, Ramiro De Leon Carpio, to complete Serrano's presidential term. De Leon, not a member of any political party and lacking a political base, but with strong popular support, launched an ambitious anti-corruption campaign to "purify" Congress and the Supreme Court, demanding the resignations of all members of the two bodies. Despite considerable congressional resistance, presidential and popular pressure led to a November 1993 agreement brokered by the Catholic Church between the government and Congress. This package of constitutional reforms was approved by popular referendum on January 30, 1994. In August 1994, a new Congress was elected to complete the unexpired term. Controlled by the anti-corruption parties--the Populist Republican Front (FRG) headed by ex-General Efrain Rios Montt, and the center-right National Advancement Party (PAN)--the new Congress began to move away from the corruption that characterized its predecessors. Under De Leon, the peace process, now brokered by the United Nations, took on new life. The government and the URNG signed agreements on Human Rights (March 1994), Resettlement of Displaced Persons (June 1994), Historical Clarification (June 1994), and Indigenous Rights (March 1995). They also made significant progress on a Socio-economic and Agrarian Agreement. National elections for President, the Congress, and municipal offices were held in November 1995. With almost 20 parties competing in the first round, the presidential election came down to a January 7, 1996 runoff in which PAN candidate Alvaro Arzu defeated Alfonso Portillo of the FRG by just over 2% of the vote. Arzu won because of his strength in Guatemala City, where he had previously served as mayor, and in the surrounding urban area. Portillo won all of the rural departments. The biggest surprise of the election was the strong showing of the newly formed New Guatemala Democratic Front (FDNG), the first legitimate party of the left to compete in 40 years. The FDNG presidential candidate won almost 8% of the vote, and six FDNG deputies, including several internationally known human rights advocates, were elected to Congress. In the other November races, the PAN won 43 of the 80 seats in Congress and leadership of one-third of the municipal governments. The FRG won 21 seats to become the principal opposition party. The formerly powerful but discredited DCG and UCN elected only seven deputies between them. Guatemala's 1985 Constitution provides for a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. The 1993 constitutional reforms included a reduction in the number of congressional representatives in the unicameral structure, from 116 to 80, and an increase in the number of Supreme Court justices from nine to 13. The terms of office for president, vice president, and congressional representatives were reduced from five years to four years and for Supreme Court justices from six years to five years. The president and vice president are directly elected through universal suffrage and limited to one term. Supreme Court justices are elected by the Congress from a list submitted by the bar association, law school deans, a university rector, and appellate judges. The Supreme Court and local courts handle civil and criminal cases. There also is a Constitutional Court. Guatemala has 22 administrative subdivisions (departments) administered by governors appointed by the president. Guatemala City and 330 other municipalities are governed by popularly elected mayors or councils. National Security Guatemala is a signatory to the Rio Pact and is a member of the Central American Defense Council (CONDECA). The president is commander-in-chief. The Defense Minister is responsible for policy. Day-to-day operations are the responsibility of the chief of staff and the national defense staff. An agreement signed in September 1996 (which is one of the substantive peace accords), mandated that the mission of the armed forces change to focus exclusively on external threats, although President Arzu has ordered the army to support the police in response to public concern about a nationwide wave of violent crime. The accord calls for a one-third reduction in the army's authorized strength and budget, and for a constitutional amendment to permit the appointment of a civilian Minister of Defense. The army has met its accord-mandated target of 33,000, including subordinate air force (1,000) and navy (1,000) elements. It is equipped with armaments and materiel from the United States, Israel, Yugoslavia, Taiwan, Argentina, Spain, and France. As part of the army downsizing, the operational structure of 19 military zones and 3 strategic brigades are being recast as several military zones are eliminated and their area of operations absorbed by others. The air force operates three air bases; the navy has two port bases. Principal Government Officials President--Alvaro

ARZU Irigoyen The Guatemalan Embassy is at 2220 R Street, NW, Washington, DC 20008 (tel. 202-745-4952). Consulates are in New York, Miami, Chicago, Houston, and Los Angeles, and an honorary consul in New Orleans. Upon taking office, the Arzu Administration made resolution of the 36-year internal conflict before the end of 1996 its highest priority. President Arzu took the bold steps necessary to breathe life into the peace process and to increase civilian control over the military. He traveled to Mexico and El Salvador to meet with guerrilla leaders, thus adding impetus to the peace process and leading to subsequent agreements on: socio-economic/agrarian issues which were signed in May; the strengthening of civil society and the role of the military in a democracy in September; a definitive ceasefire, constitutional and electoral reforms, and an agreement on the reinsertion of the URNG into political life in Guatemala in December. The final agreement, signed on December 29, 1996, contributed significantly to an improvement in Guatemala's human rights (see last page for summary of main substantive accords). Within two weeks of taking office, President Arzu initiated a major shakeup of the military high command and oversaw the firing of almost 200 corrupt police officials. In September 1996, the government uncovered a large smuggling scheme involving a number of government officials and military and police officers. The case, which is expected to take a number of years to resolve, resulted in the dismissal of several additional military, police, and customs officials. The Arzu Administration also began a series of actions to boost the economy, including a reform of the tax system, and demonopolization and privatization of the electricity and telecommunication sectors. President Alvaro Arzu has strongly and publicly condemned human rights abuses. Positive political developments and the demobilization of 200,000 members of the Civilian Defense Patrols were major factors in the positive change. In contrast to past years, there was a marked decline in new cases of human rights abuse, but problems remain in some areas. Common crime, aggravated by a legacy of violence and vigilante justice, presents a serious challenge to the government. Impunity remains a major problem, primarily because democratic institutions, including those responsible for the administration of justice, have developed only a limited capacity to cope with this legacy. The human rights accord signed in March 1994 called for the immediate establishment of a UN Human Rights Verification Mission in Guatemala (MINUGUA), which began to operate in November 1994. The presence of MINUGUA has been a highly positive factor in improving respect for human rights. Guatemala's GDP for 1997 is estimated at $16 billion, with real growth of approximately 4%. The government has initiated a number of programs aimed at liberalizing the economy and improving the investment climate. After the signing of the final peace accord in December 1996, Guatemala is well-positioned for rapid economic growth over the next several years. Guatemala's economy is dominated by the private sector, which generates about 85% of GDP. Agriculture contributes 24% of GDP and accounts for 75% of exports. Most manufacturing is light assembly and food processing, geared to the domestic, U.S., and Central American markets. Over the past several years, tourism and exports of textiles, apparel, and non-traditional agricultural products such as winter vegetables, fruit, and cut flowers have boomed, while more traditional exports such as cotton, sugar, and coffee continue to represent a large share of the export market. The United States is the country's largest trading partner, providing 44% of Guatemala's imports and receiving 31% of its exports. The government sector is small and shrinking, with its business activities limited to public utilities (which are to be privatized) and several development-oriented financial institutions. Current economic priorities include:

Import tariffs have been lowered in conjunction with Guatemala's Central American neighbors so that most now fall between 1% and 20%, with further reductions planned. Responding to Guatemala's changed political and economic policy environment, the international community has mobilized substantial resources to support the country's economic and social development objectives. The United States, along with other donor countries--especially France, Italy, Spain, Germany, Japan, and the international financial institutions--have increased development project financing. Donors' response to the need for international financial support funds for implementation of the peace accords is expected to be good. Problems hindering economic growth include illiteracy and low levels of education; inadequate and underdeveloped capital markets; and lack of infrastructure, particularly in the transportation, telecommunications, and electricity sectors. The distribution of income and wealth remains highly skewed. The wealthiest 10% of the population receives almost one-half of all income; the top 20% receives two-thirds of all income. As a result, more than half the population lives in poverty, and two-thirds of that number live in extreme poverty. Guatemala's social indicators, such as infant mortality and illiteracy, are among the worst in the hemisphere. Guatemala's major diplomatic interests are regional security and, increasingly, regional development and economic integration. The Central American Ministers of Trade meet on a regular basis to work on regional approaches to trade issues. In March 1997, Guatemala hosted the second annual Trade and Investment Forum, under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Commerce. The two-day event highlighted the growing relationship that Guatemala has with its closest trading partners and offer regional opportunities to foreign investors. In March 1998, Guatemala joined its Central American neighbors in signing a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA). Guatemala also originated the idea for, and is the seat of, the Central American Parliament (PARLACEN). Guatemala participates in several regional groups, particularly those related to the environment and trade. For example, President Clinton and the Central American presidents signed the CONCAUSA (Conjunto Centroamerica-USA) agreement at the Summit of the Americas in December 1994. CONCAUSA is a cooperative plan of action to promote clean, efficient energy use; conserve the region's biodiversity; strengthen legal and institutional frameworks and compliance mechanisms; and improve and harmonize environmental protection standards. Guatemala long laid claim to Belize; the territorial dispute caused problems with the United Kingdom and later with Belize following its 1981 independence from the U.K. Relations have since improved. In 1986, Guatemala and the U.K. re-established commercial and consular relations; in 1987, they re-established full diplomatic relations. In December 1989, Guatemala sponsored Belize for permanent observer status in the Organization of American States (OAS). In September 1991, Guatemala recognized Belize's independence and established diplomatic ties, while acknowledging that the boundaries remained in dispute. Although Belize has recognized Guatemalan diplomatic representation at the ambassadorial level for several years, the Guatemalan Government did not accredit the first ambassador from Belize until December 1996. While Belize continues to be a difficult domestic political issue in Guatemala, the two governments have quietly maintained constructive relations. The Arzu Administration has indicated its intent to resolve the dispute with Belize, making it the number one priority now that the final peace accord has been signed. In anticipation of an effort to bring the border dispute to an end, in early 1996, the Guatemalan Congress ratified two long-pending international agreements governing frontier issues and maritime rights. Relations between the United States and Guatemala traditionally have been close, although at times strained by human rights and civil/military issues in earlier periods. U.S. policy objectives in Guatemala include:

The United States, as a member of "the Friends of Guatemala," with Colombia, Mexico, Spain, Norway, and Venezuela, played an important role in the UN-moderated peace accords, providing public and behind-the-scenes support. The U.S. strongly supports the six substantive and three procedural accords, which, along with the signing of the December 29, 1996 final accord, form the blueprint for profound political, economic, and social change. In Costa Rica in May 1997, President Arzu met with President Clinton and his counterparts from Central America, Belize, and the Dominican Republic to celebrate the remarkable democratic transformation in the region and reaffirm support for strengthening democracy, good governance, and promoting prosperity through economic integration, free trade, and investment. The leaders also expressed their commitment to the continued development of just and equitable societies and responsible environmental policies as integral elements of sustainable development. Tangible support for the implementation of the accords will come from a number of sources. Development assistance through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is concentrated in programs to strengthen democratic institutions, improve health and education, and protect the environment. The U.S. will also provide up to $25 million dollars in FY 1998 Economic Support Funds, including an immediate grant of $5 million, focused on the most immediate needs associated with the implementation of the peace accords, such as demobilization of the ex-combatants. The U.S. hopes to be able to continue this level of support for another two years. To address the issue of impunity, USAID and the Department of Justice are funding programs to strengthen the courts, the public prosecutor's office, and the civilian police. Other federal agencies such as the Departments of Agriculture, Labor, and the Treasury have programs either in place or in the planning stages to support specific aspects of the peace accords. The U.S. Government suspended military aid to Guatemala in 1977 following an upsurge in death squad activity and the publication of the Department's first human rights report. Modest training assistance was reinstated in 1983, but suspended again in 1990 in response to the murder of U.S. citizen Michael Devine and the Guatemalan military's lack of cooperation in that investigation. The U.S. Government eliminated access to IMET funds in 1995 over human rights concerns. Currently, Guatemala is eligible for expanded IMET and a program began in 1997. The United States is Guatemala's largest trading partner, providing 44% of the country's imports and receiving 31% of its exports. U.S. official assistance to Guatemala since 1986 totals about $965 million, and in 1997, the U.S. provided $65 million in bilateral economic development assistance. More than 150,000 U.S. citizens visit the diverse attractions in Guatemala each year, although as stated in the Consular Information Sheet for Guatemala, "While violent crime has been a serious and growing problem in Guatemala for years, 1997 has seen a marked increase in incidents involving American citizens." When visitors have problems, their first contacts are often with the U.S. Embassy. Whether it is replacing a lost passport, arranging for additional funds to be wired to a visitor in distress, or assisting in locating a lost loved one, the embassy is prepared to help American citizens traveling in Guatemala. Likewise, American businesses find a relatively open and accommodating market in Guatemala, which is particularly receptive to U.S.-origin products. Fifty U.S. businesses have set up assembly plants, while other investors are finding an attractive climate in which to establish their companies. Principal U.S. Embassy Officials Ambassador--Donald

J. Planty The U.S. Embassy in Guatemala is located at Avenida la Reforma 7-01, Zone 10, Guatemala City (tel. (502) 331-1541); fax (502) 331-8885) This information is courtesy of the U.S. Department of State, March 1998

|

||||||||

|

To comment on this service, send feedback to the Web Development Team. |

||||||||